Every writer knows the dance: you open the document, line up your snacks and your playlist, and then… nothing. A blinking cursor, a dozen good intentions, and not a single sentence that feels safe to type. The problem isn’t talent. It’s pressure. We try to write a finished book in the first paragraph. No wonder our hands don’t move.

The easiest way through is smaller and simpler than it sounds. You don’t need a perfect outline or the right mood; you need one scene that exists. Once you have that, the rest of the draft has somewhere to grow from. The trick is learning how to start a scene without waiting to feel ready.

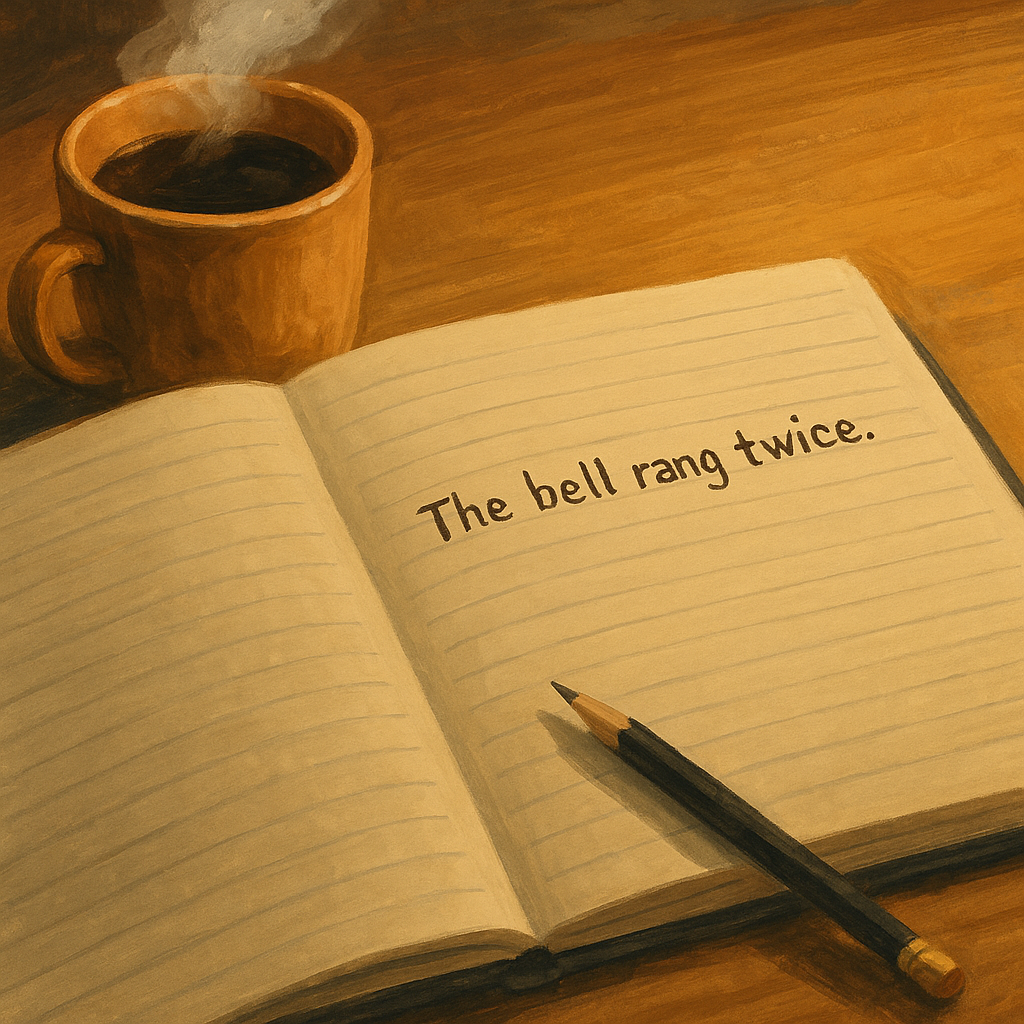

I use a tiny routine I call the “first scene sprint.” Pick one point of friction—something that forces your character to act now. It can be as ordinary as a phone that won’t stop ringing or as dramatic as a knock at 3 a.m. The only rule is that it changes what your character planned to do today. Put that pressure on the page in the very first line. Don’t warm up or explain the world. Start with movement and let yourself figure out the context as you go. You’re writing a door opening, not a museum tour.

Once you’ve got motion, give the character a simple target for the next few minutes of story: get the door open, hide the letter, make the call, say the thing they’ve avoided saying. You don’t need to name a theme or map three acts. Just aim the scene at a small win or a small loss. If you feel yourself slowing down to research a street name or invent a perfect backstory, leave a bracket like [street name TK] or [why she hates hospitals] and keep going. Brackets are permission slips for your future self; they let the present you stay in the moment.

Momentum lives in verbs, so let them carry you. Instead of telling us the room is beautiful, let the window flare, the curtain snap, the cup clatter. You’re not avoiding description; you’re letting action do the describing. Dialogue works the same way. Keep it short, let the subtext do the heavy lifting, and sprinkle a few beats—hands on a doorknob, a coat shrugged off, a chair not quite tucked in—to show what people are feeling without speeches. If a line starts to turn into a monologue, cut it in half and put the rest in the next line of action.

Here’s what this looks like when you’re actually writing:

The bell rings twice and then someone hits it like they’re done asking nicely. Mara wipes her hands on the dish towel and doesn’t call out. The hallway is narrow enough that you can hear a person breathing if you care to listen. She does, and hears it: fast, like running, like news. She unlatches the chain and keeps the door mostly shut. “You can leave it,” she says. The voice on the other side doesn’t leave anything. “You changed your number,” he says. She opens the door the rest of the way, because now the scene can’t stay in the hallway.

That’s not a full story. It doesn’t need to be. It’s a live wire on the page. You can feel where it goes next because the scene set itself a task: who is “he,” why is he here, and what will it cost for her to let him in or send him away? Your job in a first draft isn’t to answer everything; it’s to keep the moment alive long enough to find out.

End the sprint before you run out of steam. Stop mid-beat if you can: one sentence into the next action, one breath before the decision. Tomorrow’s you will sit down and finish that sentence without the usual hesitation. That small trick—stopping with momentum—saves more projects than any fancy software ever will.

After you’ve got a scene, resist the urge to polish it into marble. Give it a quick read to catch obvious snags—who’s where, who’s speaking, what changed by the end—and leave the pretty sentences for later. A readable, slightly messy scene is worth a hundred gorgeous fragments that never connect. You’ll be surprised how often a “good enough” first pass contains the bones of your best work: a verb you didn’t overthink, an image you didn’t smother, a line of dialogue that sounds like an actual person.

If you’re the kind of writer who needs permission, here it is: you are allowed to write badly while you’re writing bravely. The blank page isn’t asking for brilliance; it’s asking for a place to start. Give it a knock at the door, a phone that won’t stop, a promise your character can’t keep. Twenty minutes later, you’ll have a scene that exists—and a draft that finally has somewhere to go.

Leave a Reply